Theodore Adorno, the literary critic, wrote in the wake of the Second World War that, “After Auschwitz no poetry.” Beyond the powerful point Adorno makes regarding the frivolousness of the garden variety lyric and the mundane weakness of the liberal poem that is being called into question, the Holocaust has haunted Twentieth and even the Twenty-first century poetry.

One is reminded of the writings of Paul Celan and individual poems by Czeslaw Milosz, Geoffrey Hill (both onlookers to the atrocities) and the Jewish American poet, Anthony Hecht, who was one of the first US soldiers to pass through the gates of Flossenbűrg concentration camp.

Celan and Hecht were eyewitnesses, one a prisoner and the other a soldier who was shocked at the horrors of what he witnessed. When I met Hecht, fifty years after he arrived as a liberator of the camp, he would not speak of his experiences. He said they were too difficult; yet some of his best poems address the complexities and the immoral absurdities of what he saw. The reality of Celan and Hecht’s poems is reportage. The question facing a poet in this situation is how does one speak of such things without creating an aura of the pornography of violence?

Many American poets perceived the horrors as the death of gentility – a moot point at best articulated by A. Alvarez in his essay “Against the Gentility Principle” which, when put into practice became a solipsistic manifesto of self-destruction. That stance completely missed the point. The Holocaust was not about suicidal academic poets. It was an event that murdered real people who deserve to be remembered for their humanity, for their love, and for the simple things they experienced in life such as milk tea.

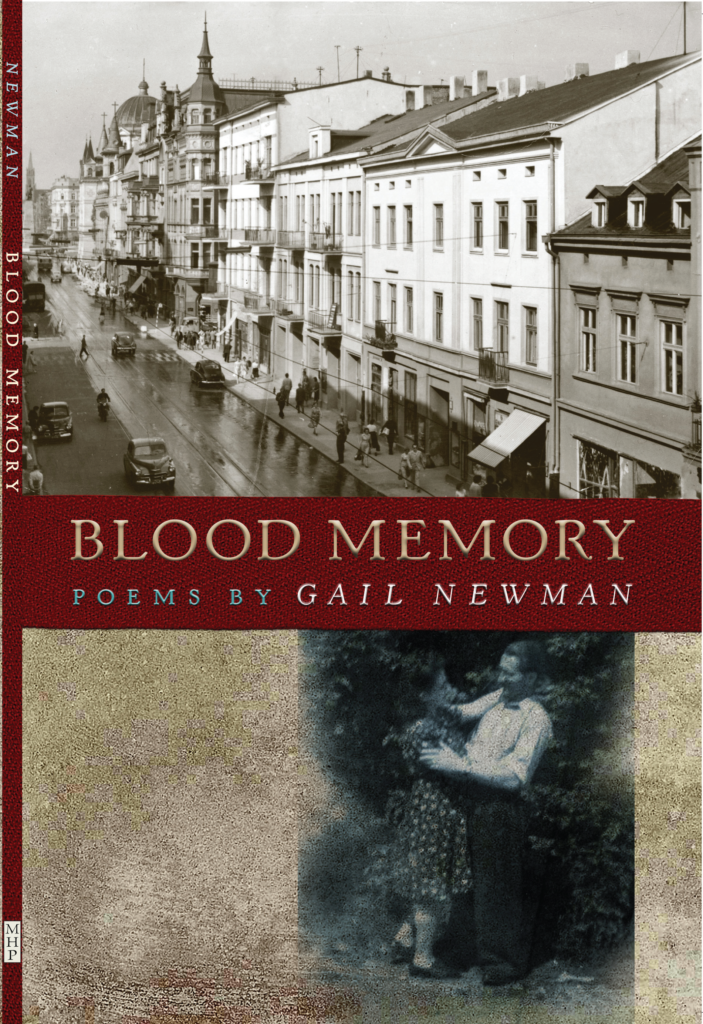

In her collection of poetry, Blood Memory, Gail Newman creates a testament of her family’s ordeal in the holocaust. Her family members are people with faces – a point the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas made after losing his entire family in the Holocaust and finding that humanity’s failure resided in its inability to see the face of God in each individual. The poems in this collection are intimate. Newman tells their story, but the narrative is not an exercise in psychoanalysis. It is a kaddish spoken with love.

Gail Newman has found an answer. She humanizes the victims of the Holocaust, gives them names, faces, personalities, and family connections. In the case of Newman, she has undertaken the difficult take of reconstructing the fates and experiences of family members to produce a book of stunning poetic work. Her strongest poems are the ones where narrative is secondary to intimacy such as “Taken.” In poems such as “After the Hanging,” the idea that the band can continue to play despite the murder that has taken place is directly defiant to the notion of resignation of art. Art is human and Newman continuously asserts that human beings survived despite unimaginable horrors. The bravery that resides in the children “not looking away,” makes a powerful and convincing point that poetry is not dead: it is looking the worst demons of humanity in the eye and refusing to back down.

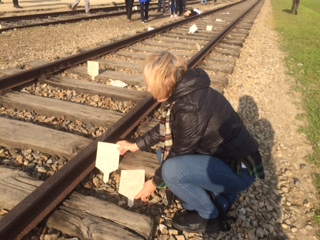

In the sequence of Łódź poems about her mother’s nightmarish experiences in the ghetto, Newman balances the small acts of living to survive with the fears and perils of not surviving. Newman states, very subtly, that survival is not merely finding ways to stay alive but an expression of resistance, a response to reality that is not courage but the refusal at the heart of life that says, “I will not die. I will not cease to be a human being.” In “Homecoming,” she sums up that courage: “No, No, and again, No. Words she would carry with her.” Blood Memory is a reconstruction of what it means to refuse to die.

Gail Newman has worked as an arts administrator, museum educator at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, and CalPoets poet-teacher and San Francisco Coordinator. She was co-founder of Room, A Women’s Literary Journal and has edited two books of children’s poetry: C is for California and Dear Earth. A collection of her poetry, One World, was published by Moon Tide Press.