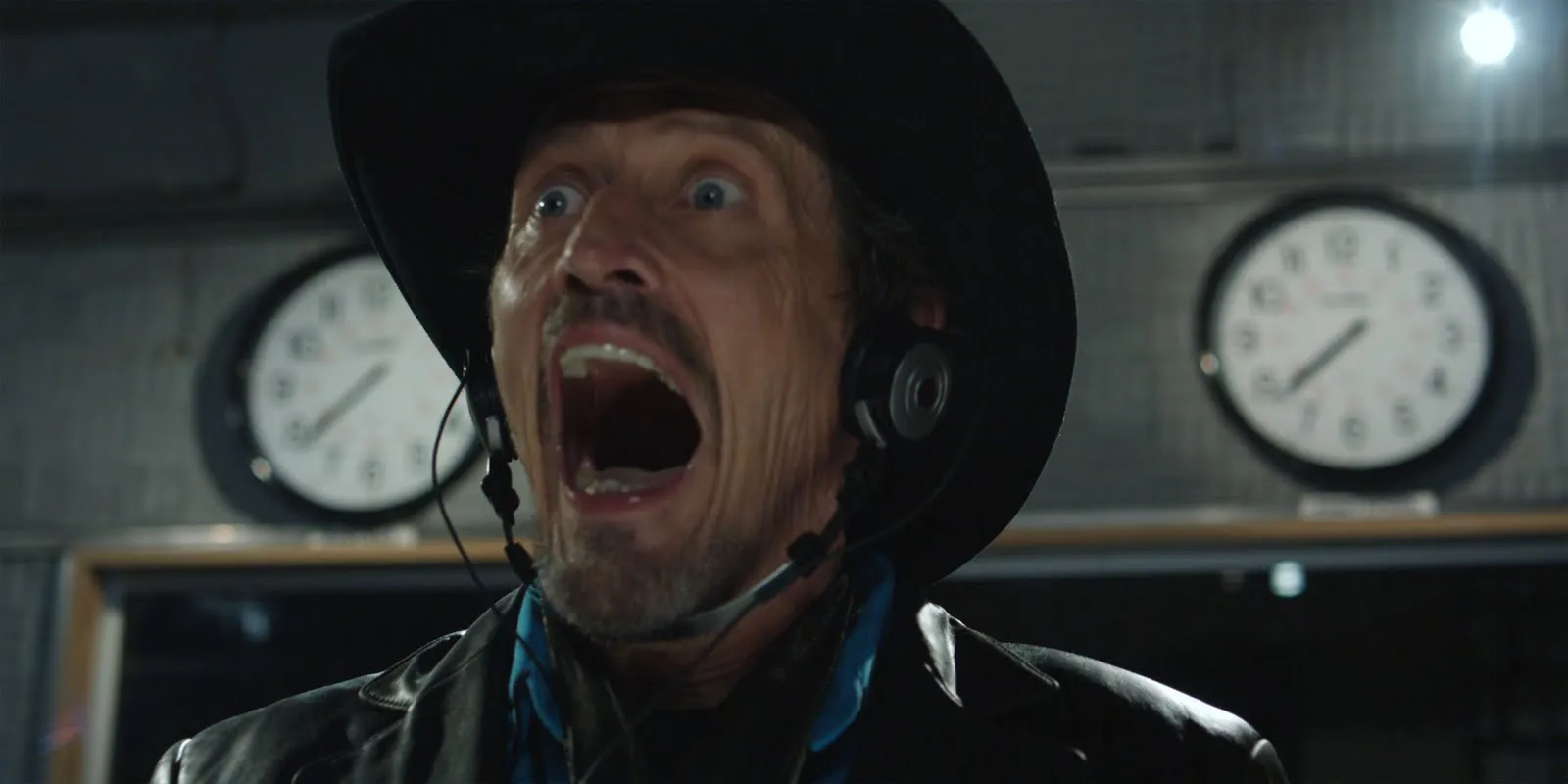

Stephen McHattie as Grant Mazzy in ‘Pontypool’ (2008)

In 1959, the world was shaken up when a man, not afraid to push the limits of human imagination, was born in Toronto. Tony Burgess does not only write unique fiction — he embodies unique fiction. Where some authors may draw a line at exploring the deepest expanses of human depravity, Burgess delights in blurring those lines and creating subversively uncomfortable narratives. His arguably most popular work, Pontypool Changes Everything, found tremendous success as both a novel and later as through the film adaptation Pontypool, proving that Burgess’s talents translate over to the big screen as well.

Other notable Burgess works include, but are definitely not limited to, his experimental The N-body Problem which explores the seemingly mundane issues of waste disposal during a zombie apocalypse, and the perplexing narrative of Idaho Winter that follows a young protagonist who becomes self-aware of his status as a character in a novel. Though one cannot forget the movie Septic Man, with it’s screenplay written by Burgess where a man gets trapped in a septic tank only to undergo a horrifically monstrous transformation — a movie that impressively landed on some certain lists for worst movies of all time, a fact that Burgess considers to be a proud accomplishment. Among some of his other, perhaps more mainstream, accomplishments include Pontypool being shortlisted for Best Adapted Screenplay at the 2010 Genie Awards, Ravenna Gets winning the 2011 ReLit Award, Idaho Winter being shortlisted for the 2012 Ontario Trillium Book Award, and quite recently critically acclaimed director Guillermo del Toro expressed his admiration for Pontypool on Twitter.

Tony Burgess continues to provide his gift of authentic storytelling to the world, embracing vulgarity and chasing abnormality while often incorporating comedy into his horror for an unsettling experience. My experience chatting with Tony was lovely, and I consider it a privilege to share his eccentrically brilliant mind with the world.

You’ve written quite a lot of zombie fiction, ranging from the notable “Pontypool Changes Everything” to “The n-Body Problem.” Is there anything in particular that attracts you to exploring this undead, apocalyptic subgenre?

I’m a bit of a horror fan anyway and sort of grew up through it and never losing it in my first fascination for storytelling, regardless of how ridiculous and insane the story is. When I wrote Pontypool in 1995, zombies weren’t a popular thing. One of my favorite films of all time is Night of the Living Dead, along with some Italian zombie films and the Hurk Harvey film Carnival of Souls. So those films were in my imagination when I started writing and pulling apart genre fiction and going nuts on it. One of the first sort of things I thought of was zombies, and I guess as it goes on it’s obviously evolved for me in a lot of different ways.

But what I like about zombies is that, like most other horror figures in fiction or film, there’s always an allegory. There’s always a metaphor. Which I find sort of interesting because how meaningful that is gets exhausted pretty quickly, and then you’re stuck with a kind of a meaning-making mechanism that’s out of control in the world. I liked that idea that’s it’s undead, it’s a dead metaphor or a dead allegory that’s stomping around and still taking lives, and then you’re going to need an allegory or a figure that helps you understand the dysfunction. I just liked the possibility of zombies and their meaning less than meaninglessness, their unmaking of meaning and undeadness.

Though now I think we’re saturated with this idea. The interest is sort of minimal, and it was by the time I got around to The n-Body Problem, which is kind of a non zombie story. One of the big draws to the Romero zombie is the slow, sluggish, brain dead zombie on its own, that a 14 year old can probably dispatch it. But it’s when you have thousands of them thronging that they become dangerous. So they’re not really dangerous on their own. So I thought with The n-Body Problem, what if they weren’t even dangerous at all? Would that still be horrifying if all they really did was move a little bit and lay on the ground.

A review of your book “The n-Body Problem” in The National Post claimed “the book is a finely wrought and exciting work, but one that has the capacity to disarm, disgust and profoundly distress.” Do you consider this a compliment? How does disarming, disgusting, and distressing your audience make your overall message more impactful?

Oh, that’s absolutely what I’m trying to do, and I’ve always done that. What I’ve always tried to do is create something that behaves in a way that you feel it may be dangerously out of control in my head. When I put it into my head, my head is dangerously out of control of my thoughts. That was actually part of the basis of the Pontypool virus, it was supposed to be a real vivid version of that, that certain ideas in a certain order read on a page will disorder your thoughts or create such kind of revulsion at the word that you have a physical reaction. In fact, the editor of The N-body Problem told me that after she had finished her first edits, she spent a week in bed with red wine. She was so traumatized, and that makes me very happy.

The film that I wrote called Septic Man has the disclaimers of gore, sexual content, etc., but in the states it was something like immoral and blasphemous imagery. It was something I’d never read before, they had obviously struggled to describe why you shouldn’t see this movie. Septic Man was also number seventeen on a “50 Worst Movies of All Time” list, which makes me very, very happy.

So that has always been a goal to, not just make the reader uncomfortable, but to make the reader feel like they’re not in control of their own thinking, and that there is a possibility that they sense that this could go further and I won’t be able to come back from it. Some of that comes from the mid-1970’s when the first sort of wave of horror came out and in video stores and there was a whole section of films that are now classics, but at the time were just like the most exploitative, low rent, cheap B movies imaginable, like The Toolbox Murders, Phantasm and Sleepaway Camp. What always freaked me out was it wasn’t so much that you were seeing cheap gore gags, but what used to upset me is that I felt like the people involved in making it were not well, and they had wanted to do this to me, that it’s an expression of the desire of the person making it. The limitations that you’re seeing on the screen are not limitations in their imagination, so they are terrifying to me. That was part of the thing I was trying to do with fiction as well. To be one of those types of makers, a maker you don’t ever want to meet, or at a certain point don’t trust that they have your sanity in mind.

You worked on the screenplay for the adaptation of your novel “Pontypool Changes Everything” into the 2008 film “Pontypool.” How was the transition from novel writing to writing screenplays? Do you prefer one medium of writing over the other, or do they each have their own distinct appeal?

I don’t necessarily prefer one over the other. They’re very different, not from the point of view of how you’re going to tell the story necessarily. When you’re writing a novel you’re writing it completely on your own, so you have the kind of luxury, or pain, of doing it, or not doing it, on any given day. You can just be a bit more reckless in constructing it, which is very nice. The thing about novel or fiction writing is that it’s an expensive thing to do because you don’t really make much money on it.

Screenwriting does afford an income, which is okay. But then you do have to work with a committee, and that’s something that takes a lot out of me, because I’m reckless and they don’t like that, but they also will hire me because they want it. It’s so weird. They’ll ask me to write some crazy stuff, and when I do it they’ll then turn around and say I don’t know about the crazy anymore. So you have those conversations, which can go south or they can be worked out. For the Pontypool movie, I had been writing screenplays at that point for a number of years, so I knew more or less formally what to do with them. I knew sort of the main building blocks of what makes a screenplay work.

So I knew that stuff, but Bruce [McDonald] just let me go nuts, and I think it worked out. It’s been difficult trying to get that kind of scenario back again. Certain producers want an adaptation done much more strictly; they want it to resemble the book closely. One of the producers I worked with was almost compulsive about it, down to the page number lining up with specific scenes. I didn’t mind, because I’ve done quite a bit of writing for hire and commission script work. I liked being relieved of having to make choices based on my own impulses, which are sometimes destructive and a little untenable. Though I ended up doing pretty well with it and appreciated having that kind of restraint stuck on me.

Interestingly enough, The n-Body Problem and Cashtown Corners were meant to be long treatments for films. Since I was doing a lot of work in commissioned screenplay writing I was sorta thinking, “wow man, I need to write some books,” cause I hadn’t done that in awhile. But I also want to make them into movies because you get into a thing where you think that’s where they should go, everything should be in a movie. So I thought, what if I wrote them as if they were like 200 page treatments? Then when it comes down to writing the screenplay, it’s all there.

So in a way that sort of works differently than Pontypool for instance, which I more or less had to completely throw the book away to write [the screenplay] because those are the choices you make. The film was actually commissioned by the CBC as a radio play. It was pitched to them, and it sounds easy to do, like a War of the Worlds thing, we’ll have the whole thing happening on air. So, I mean, that was the sort of germ of that. Though obviously it can’t be a section of the novel because it doesn’t happen in the novel. But we took some elements and put them in there. I felt sort of free because I was the author, so I could just throw the book away and say, “well, this is a chapter from the book that I didn’t write.”

I’ve also adapted Idaho Winter a couple of times, and it’s now in a very interesting form with a director. We’re making the rounds again, finding out if there’s anybody interested in funding or producing. The story is never really over as far as that goes, but it’s only on when it’s on. It’s very hard to get a movie made, it’s a very complicated uphill battle.

Your work often transcends and reinvents the traditional tropes of the horror genre, playing around with complex themes and narrative structures. Where do your unique ideas come from? What advice would you give to writers who are struggling to think outside of the box while writing in a stagnant genre?

One of the things that started me writing and, and stopped me writing, was thinking that I was very good. I don’t think it helps you to think that you’re very good or to think that you need to be very good. I think it’s more important that you start something and follow where it goes without thinking critically about how you’re writing or whether it’s any good. I do that through automatic writing, just to write credibly fast and to ignore things like punctuation and look for rhythms in the things you’re saying while listening to the sounds of the things you’re writing. Don’t worry whether it’s crap. I think that one of the big causes of writer’s block is thinking you’re better than you are.

I think writing should be more like life drawing in that you do hundreds and hundreds of drawings without really even looking at the page, but you’re looking at the model and what that process is doing is destroying the habits you had that told you you were good. So I think you have to do that with writing. You must destroy your writing habits that first impressed the people who read your work and said it was good. I did that before I wrote Ponypool, I walked around Parkdale, a small area in Toronto, and I went onto a street and I stood in front of the first house and I automatically wrote a page about what I thought was happening in the house and about the house itself. Then did the next house, the next house and the next house and the next house. It was what I call “killing-time writing.” How long can you spend on a page with someone standing at a bus-stop when you don’t know where they’re going or where they’ve come from? Those sorts of exercises work really well as far as destroying the things that you think you do well, and that’s important.

With something like genre busting or trope forming, you discover those kinds of things once you open up what’s possible on the page. Really be careful about, and be aware that, the good thing that you think is good is good because it’s cliche. If you do use a cliche, you should use it as a cliche.

You have a degree in semiotics from the University of Toronto, how has this education influenced your creative writing?

I went to a couple of different art schools when I was younger and started in painting, drawing, some sculpture and performance stuff, installations and things like that. After I got out I did that for about 10 or 15 years, and used to use writing as a support for all of that, doing a lot of readings in clubs and places. But my priority was visual art. I ended up going back to university for the first time, but I was quite a bit older, I was like 30, so it was like my second or third career. I encountered the idea of Canadian lit and national literature fairly late. I didn’t know all of these people around me were publishing books and magazines, holding these soirees and whatnot, so that was new to me. As I sort of started to get a handle on the science of semiotics and the application of it, it immediately translated into things that I could make rather than a way of understanding the things I consume. So for me, it was a crude practical tool for creating new rules for making things. So I was fairly old when I was first published, even though I’ve been writing since I was five.

Though if I read something an author has written, I understand what they’re doing in regards to a certain theoretical model, it immediately becomes uninteresting to me because it looks so much like an exercise and it looks coherent. It’s accounting for everything in the method it’s using. Maybe it comes from my feral painting days, but I really do like when it’s almost a low-tech technology on the verge of falling apart. We’re at the point where this breaks, and you’re in danger of hearing noises and feeling chaos.

You recently lectured at the Miskatonic Insitute of Horror Studies, a seminar entitled: The Holocaust and Its Double: Writing Fiction in the Medium of Genocide. How was the experience of sharing your knowledge with the next generation of aspiring horror and thriller writers?

That was such an overwhelming subject, and I knew that when I started it up, it was going to be a scarring and despairing experience to spend a lot of time on that material. To think for yourself in that material takes a great amount of work. I went through a series of stages. After I finished writing Idaho Winters, I was approached by a Jewish producer who said to me, “you realize that this book is about the persecution of Jews in Europe and growing up Jewish.” I said, no, I don’t know. But then we parted ways, and then another director, who was also a Jewish fellow, optioned Idaho Winters, and said “do you realize that this book is about the persecution of Jews in Europe and growing up Jewish?” At this point I said, “no, I didn’t, but I guess I did.”

After this I had to now explore this and figure out why this is being said by two different people who don’t know each other with that specific history. So I started to research and I found that as much as I knew about that particular event in history, it was nowhere near enough what I knew to come to an understanding about this. I was made despondent by it and had to understand it, and in order to understand it, I had to work very hard. So I set along into a few years of really studying it every day, taking courses at University of Israel and doing different things to find answers for myself.

I saw they were looking for people to lecture, and because [my research] had also stopped me from horror fiction for a period of time and because there is this strange connection, I thought I would tell the story of it as I’ve come to understand it because I’ve done the work. It was completely exhausting, and it took a long time to recover from it. It’s hard for me to sort of own that, I don’t know what to call it, that depression. It was a really fascinating experience, and continues to be because I continued to study it, but I feel like I don’t have that pressure to do something with it now the lecture is done.

Very early I was speaking to a friend of mine, a terrific Jewish writer, I had reached out to because nobody who wasn’t Jewish wanted to hear about it since they were so suspicious of me, questioning why are you researching this? And I couldn’t really answer readily. My Jewish friends understood better, that it had its own importance and significance. He told me early on that what you’re going to find is, as much as you’re going to know about this event, it’s also going to start to expose you. It’s going to cause you to have a start examining why you’re there and who you are, what you’re doing. That is going to be an important part of it, and I found that certainly.

Do you feel like humour and horror naturally go hand-in-hand? How do the two genre’s compliment each other and what are the advantages of mixing the two conflicting tones?

During the development of Pontypool, while Bruce and I were sitting around and reading the script, we were constantly laughing. It was constantly funny. Every scene was sort of set up for a gag or a joke. Then once we got into production, we realized that we were in danger of people thinking they were making a comedy. So we had actual signs on set that said “scary, not funny.”

My experience is that all horror is comedy, even the darkest — probably the darker, the funnier. They’re kind of slapstick jokes, and they’re brutal jokes about the brutality of living a life. So everything to me is funny, and horror is the funniest. But you don’t make it funny, if you want to make it funny, go make a comedy because that’s a whole other ball game. If you’re making a horror film, play it for keeps and make it real because that’s when the joke gets sharper, it gets honed and gets darker and deeper.

I remember when I was about 14 or 15 a friend and I were driving around on minibikes, doing our thing and the bike trail goes up beside a small highway. As we were coming in view of the highway, we saw this old man coming across the road with a bag of carrots, and a car swooped down and slammed into him. His head went bang and he went 40 or 50 feet into the air and then slid down the road on his face. So the driver got out of the car, obviously absolutely distressed, ran down, rolled him over and his whole front and face were gone. And my friend and I fell off our bikes and could not stop laughing for 20 minutes. So laughter is also a feature of shock, it’s an extraordinary place to be, just as far as a reaction to the world, a kind of joyous giddiness founded in shock.

What’s next in your creative journey?

Well, a bunch of things. During the span of COVID, lots of stop and start writing because your attention span is now deformed and distorted, your own existence is unrecognizable in a lot of ways. I ended up deciding I would just go purely automatic.

So I sat out on my front porch with my computer in the mornings and I would type non-stop from line to line. I did that for three or four months and then ended up with the novel length thing. I’d experiment with accessing different parts of my imagination to see what they were automatically doing. It’s a way of dream writing while you’re awake. I was doing that and I’m very happy with the result.

On the film front, which has been kind of exciting, I’m writing a musical. I’ve been commissioned to do this from the Collingwood Film Company. Jesse Cook, a director I’ve worked with quite a bit, and I have been kicking around the idea of doing a film about either Henry Hudson or John Franklin. I’ve got a bunch of different things worked up on Henry Hudson, because I’ve had this theory about him, but Jesse wants to do the 1812 coppermine river expedition, where Franklin was famously called the man who ate his boots. So it’s a terrific story, I’ve just been reading journals and diaries from the period and doing research. I’m very excited about that.

There’s also a couple of films coming out this year, one is called Cult Hero, it’s a kind of broad bizarro gonzo comedy about a huge cult run emasculated men who are throng together in swimming pools, praying. It’s just this weird, almost incel, kind of bizarro — and I play the leader.

The other one is a film called King of Kings, which we shot a couple of years ago. It was really going to be an interesting comedic film and again, a comedy. There’s an Elvis festival in Collingwood, it’s the second largest Elvis festival in the world only second to Memphis. But after about 25 years, the town got tired of it. And the people who run it are very closed off. They don’t want to be made fun of, they don’t want to let in any media that will mock them. There’s all kinds of rules about what media can be allowed in the town limits. We wanted to shoot a sort of punked/borat kind of thing. So me and two other guys registered as Elvis tribute artists under pseudonyms. One of our guys had actually been an Elvis tribute artist before, and the other guy was a good singer. We got in, and we wanted to take three units filming into the town, all registered as different presses that didn’t even exist. We had fake security and a fake organizer for the whole event. She was a part of our film, but she was playing the role of the organizer of the entire event.

We thought we were going to get busted right away. The first day they kind of uncovered one of our crew, our film crew, so they were run out of town. The woman who played the organizer was chased into the arena by the real security and had to hide in a bathroom stall, but it never rose to the point where they figured it out. In fact, by the end of it, the real organizer of the event was asking our organizer to take over certain functions and events, because she looked in control.

I ended up doing a song in front of like 5,000 people in town and we just had a bunch of running plots that we played out for real though. At one point I’m so nervous, I shit myself on stage and run off crying, but I had to pretend that was actually happening.

People were following me down the alley where I was weeping and the next day everybody in town is going, “oh my God, there’s that poor Elvis.” So we had this whole thing and then we pulled out, finished, and never got caught. Now that film has been cut and it just blows my mind how good it is. It’s going to be really fun, so I’m happy about that. Cult Hero will be in festivals sometime this year, and King of Kings is a sort of secret magic bullet. That’s going to come out one day.